Shinjuku's Photographer - Watanabe Katsumi by lizawa

Kotaro

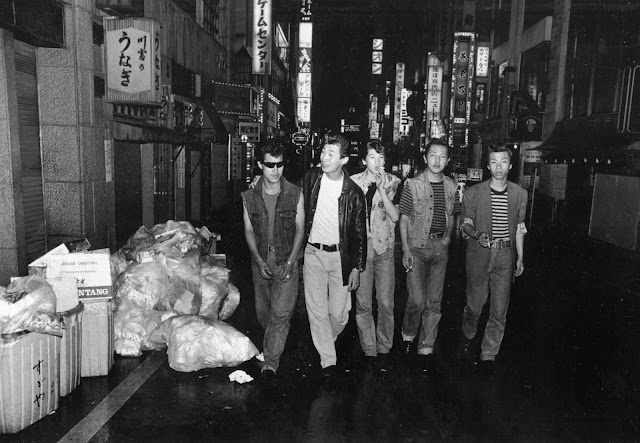

Watanabe Katsumi's workplace during the 1960s and 70s

was the living streets of Kabukicho in Shinjuku. Each night he went out into

the neighborhood, working as a photographer, taking portraits and selling them,

"three pictures for 200 yen." These pictures, in staggering volume,

cast an overwhelming spell on the viewer; they embody miraculous power.

Watanabe Katsumi was born in 1941, in Morioka City of

Iwate Prefecture, some 600 kilometers north of Tokyo. His family was poor, and

after graduating middie school, he helped support them by working as an

assistant at the Morioka City bureau of the Mainichi Shimbun, a national

newspaper. The duties of such assistants, dubbed children were varied;

sometimes Watanabe developed and printed photographs. Gradually, he became

fascinated with the medium.

Watanabe moved to Tokyo in 1962 and joined Tojo

Kaikan, the legendary portrait photography studio near the Imperial Palace. At

the time, vestiges of the apprenticeship System persisted at photo studios and

Watanabe had to survive a grueling training regimen, which began with rinsing

photo paper, before they allowed him to actually make prints himself. Once he

mastered the technique, he began to feel restless with the mechanical part of

the production process.

Around that time, he became attracted by the work of

Mr. S., an acquaintance who worked as a street photographer in Kabukicho.

Visiting S.'s room, Watanabe saw rows of photographic prints from the previous

day's work lined up on tatami mats: "They looked like money to me."

Besides S., there were three or four other street photographers who were

regulars in Shinjuku, they had worked there since World War II, when it was

hosting black markets in its ruins.

Watanabe learned the basics of the trade from S., and,

borrowing a camera and strobe light, he began working as a street photographer

in the entertainment districts of Shibuya, Shinbashi and Ueno. Soliciting bar

hostesses and cabaret busboys before working hours, he would photograph them

and sell them the prints. As his customers increased, he could no longer keep

his position at Tojo Kaikan, and in 1967, he quit his job and began working

exclusively as a street photographer.

With S.'s permission, Watanabe began to photograph in

lucrative Shinjuku. Through 1968, he commuted to Kabukicho nearly every night.

Watanabe said his peak years of success, when he produced some of his best

portraits, were between 1968 and 1970. In those days, cameras with strobe

lights were still rare and Watanabe's beautiful photographs were popular. Some

subjects wanted to send them to their families back home, others wanted to

mount them on wooden panels and hang them in their establishments. His

customers were picky about how they posed, but Watanabe was accommodating and

formed warm ties with them, as if they were family.

In the 1970s, the atmosphere of the Shinjuku streets

changed; the predominantly one or two story buildings were demolished and

replaced with taller buildings. The rich human connections that occurred in

easily accessible ground floor establishments became strained when they moved

to the upper floors. Compact cameras with built-in strobes became increasingly

popular and street photographers' customers dwindled. Watanabe's work entered a transitional period.

Shoji, the editor of Camera Mainichi, and applied to

Album 73, a Camera Mainichi, project that solicited photographs from the

general public. His acceptance leads to a significant shift in his status as a

photographer. Watanabe's seven-page spread Shinjuku Kabukicho," in the

June, 1973 issue, received the Album Prize, awarded for the best photographs of

the year, and his name became widely known.

1973 was also the year that Watanabe's first

photographic book, Shinjuku Guntoden 66/73, [Shinjuku; The Story of a Band of

thieves 66/73] published by Camera Mainichi (in association with Barakei

Gahosha) and edited by Nishii Kazuo, was realized. In January 1974 his solo

show, "Hatsunozoki Yoru no Daifukumaden" [First Peek at the Nocturnal

Demon’s Lair] dazzled visitors to the Shimizu Gallery, where innumerable photos

were pasted on every surface, including the floor and ceiling.

And yet, although his photographs were critically

acclaimed, his commercial prospects in Shinjuku did not recover. As a

consequence Watanabe temporarily stopped working as a street photographer and

sold roasted sweet potatoes in the streets. In 1976, he picked up where he had

left off and opened a small studio in Higashi Nakano, two stations away from

Shinjuku. He managed his studio for five years but continued to visit Kabukicho

at night.

After folding his studio in the early 80s, Watanabe

made ends meet with magazine assignments and successfully published tree books:

Discology, a selection of photographs he made in discotheques along with text

he wrote about h's experiences, and a revised edition of his first book

Shinjuku: The Story of a Band of Thieves, also accompanied by his own

recollections and series. They were both published in 1982 as part of a series

by Bansei-sha. And later on, in 1997, Shinchosha published a hefty, 500-page

retrospective monograph titled simply: Shinjuku 1965-97.

Anyone who sees Watanabe's photographs of Shinjuku -

especially those taken between the late 60s and throughout the 70s - will feel

powerfully drawn into that world. To help understand the energy they radiate,

the source of their charm, we cannot overlook the history of Shinjuku.

In 1698 a new station was established along the

Koshukaido Road, one of five major arteries leading from Edo (now Tokyo) to the

provinces. This is how Shinjuku was born; it flourished as a way station for

travelers, where inns jostled or space and eating and drinking establishments.

During the Meiji Era [1868-1912], railroad stations (on what are now the

Yamanote and Chuo lines) were built in Shinjuku. Later, as the private rail

lines of Odakyu, Keio and Seibu linked the city center with Tokyo suburbs,

Shinjuku developed into a leading entertainment hub. Department stores, movie

theatres, cafes, and bookstores all thrived there ; during the 1920s, Shinjuku

became the center of modernist culture in Japan.

But there was another face to Shinjuku. Before World

War II, in contrast to the celebrated world of glamorous consumer culture the

reclaimed swampland on the north side of the station had given rise to

specialty eating and drinking establishments that also provided sexual

services. Shinjuku was devastated by the war but its resurrection from the

ruins was swift. Off the main boulevards in a warren of bars, illegal

prostitutes entertained their clients on second floors, and the area came to be

known as the Blue Light district (in contrast to a Red Light district where

prostitution was legal). So, the two faces of Shinjuku, the front and the back,

the light and the dark, the commercial district and the sexual entertainment

district co-existed.

Immediately after the war, there was talk of creating

a Kabuki Theater in Shinjuku, like the original in Ginza. Although the project

never materialized the area was then dubbed Kabukicho. The idea of situating

Kabuki, already solidly established as Japanese classical entertainment near

the Blue Light district, was preposterous. Nevertheless, Kabukicho continued to

develop as a gigantic nightlife district centered on the sex trade. Along the

way, Kabukicho began to be known as Nihon no kahanshin [Japan from the

waist-down].

The Kabukicho area of Shinjuku was Watanabe's stomping

ground. He felt an affection for the hard-bitten survivors that inhabited its

streets, surviving on violence and Eros; with the sympathies of an insider

Watanabe went about his business with ease.

The subjects of Watanabe's photographs are always

clearly aware they're being photographed; their poses present their innate body

language. Watanabe was fond of saying "All Shinjuku is a stage." His

strobe managed to illuminate the essential vulnerability that lurked beneath

his subjects' blustery performance.

In the mid-1970s, as Watanabe's Shinjuku clients began

to dwindle, one of his resident models exhorted him, "Nabe-chan (his

nickname) take our pictures, save them as mementos!" Kabukicho today is

hardly recognizable as the area where Watanabe once worked as a street

photographer. Since the 1990s, as Chinese and Koreans have made their way into

the neighborhood, its population has grown increasingly heterogeneous: in some

areas forests of signs are posted in languages other than Japanese. The young

people's carefree looks, as they chatter on their cell phones and walk down the

streets, betray no trace of the past.

But step into the back alleys and there is a distinct

sense that marginal characters are still lurking about. Although significantly

reduced in scale, nightlife areas such as Golden Gai still retain vestiges of

the postwar black markets and Blue Light districts. No doubt Shinjuku will

continue to transform itself like a giant creature perpetually in flux, a fate

shared by many cultural centers of great cities.

Watanabe Katsumi died on January 29, 2006 at the age

of 64.

This essay is based on the last interview he made in

his office in Roppongi, Tokyo, on December 13, 2005.

Parmi les gangs de Kabukicho, on croise l'un des rois de Shinjuku : Terayama Shuji !